Jack Harries and Deborah Goldemberg

Open source activism

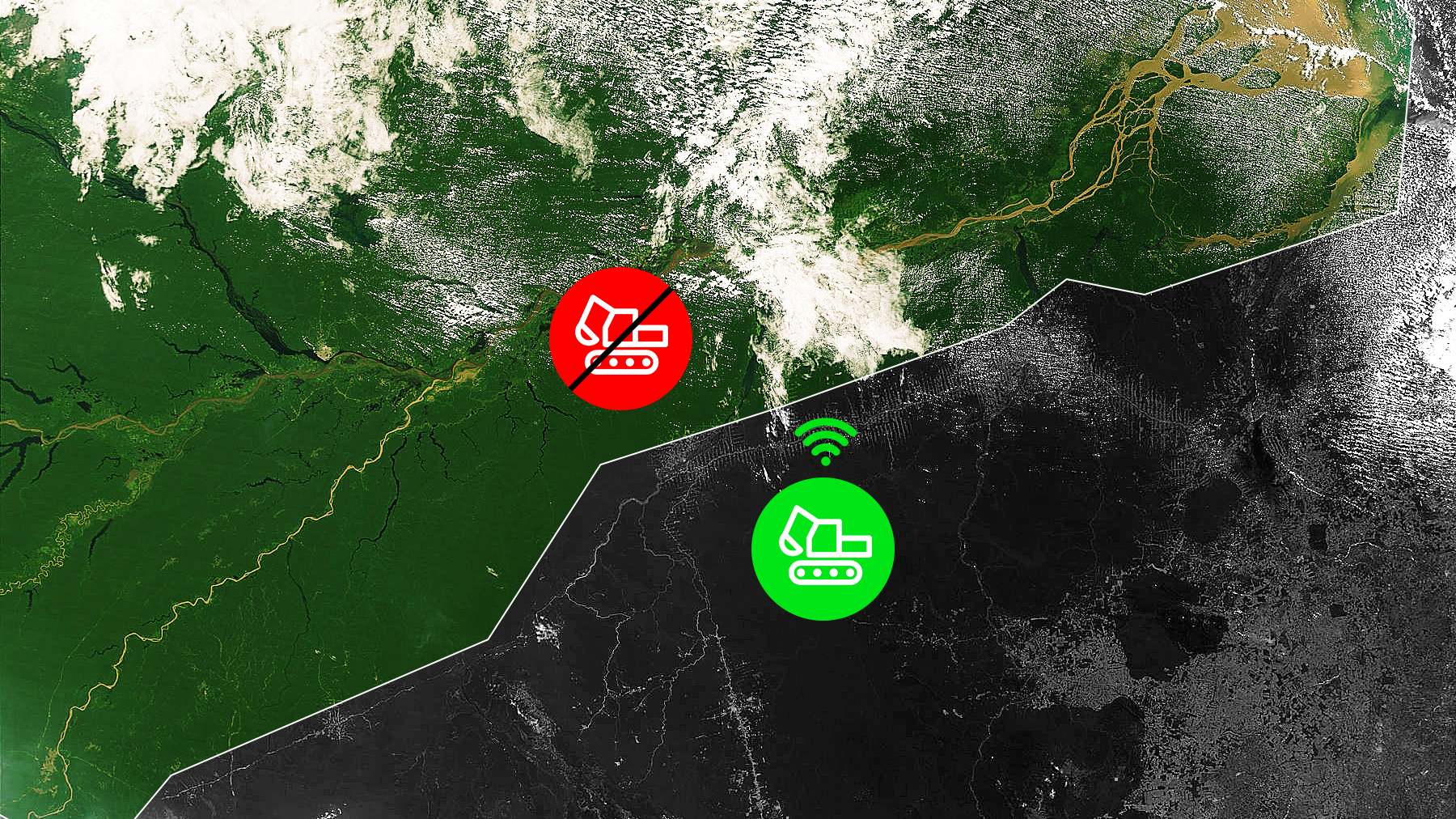

“We may not be able to stop the humans, but we can stop the machines they use.”

When an estimated one-third of the world’s protected areas are under threat of human activity, it’s essential that our actions are imminent and compelling – and as is often the case in times of uncertainty, innovation can be born out of creativity.

Over the past two years, in light of the current situation in Brazil especially where deforestation and illegal mining inside indigenous lands is a serious problem, AKQA have been working on developing an open-source software that restricts the use of heavy-duty vehicles in protected areas. Called the Code of Conscience, it has the capacity to become a cyber shield around protected areas of land and sea all over the world.

For this AKQA Insight we are joined by Jack Harries, an activist, storyteller and co-founder of Earthrise Studio, a creative platform dedicated to communicating the climate crisis, and Deborah Goldemberg, an anthropologist and sustainable development specialist from WWF. As well as Global Chief Creative Officer Hugo Veiga and Executive Innovation Director Tim Devine, two of AKQA’s creative leaders, who have been steering the Code of Conscience project since its inception.

“Design intentionality is at the core crux of Code of Conscience. We’re essentially asking manufacturers to change the intentions of products they produce so they don’t harm the places that we need to save.”

Tim Devine, Executive Innovation Director at AKQA

Real action now

Since the launch in 2019, governments, businesses and NGOs like WWF across South America have rallied together to adopt and share this initiative. The potential impact of Code of Conscience’s simple but ground-breaking technology plays into the bigger conversation about how companies can better engage in the fight against climate change. “There’s a climate emergency right now and companies understand that being good for the planet is also good for business. Those that aren’t having a positive impact in the world won’t have a place in the future,” says Hugo. “We’re helping our clients to learn how to have a better impact because their audience demand real actions now.”

Deborah recognises that while there is a lot of rhetoric from businesses about their environmental intentions, in order to translate that into actual substantial change greater awareness needs to be raised about the reputational, not to mention financial, risks for companies who don’t conform. “A key to this is compromise,” she says. “New opportunities and new markets generated in this area need to be pointed out so that a company’s profit margins aren’t affected.”

Tools for today

Today’s youth are tomorrow’s leaders and Jack typifies how the next generation are taking the initiative to make the conversation around climate change unavoidable. “Previous generations have found a way to separate themselves from the environment but we’re seeing it being put back into the centre of policy,” says Jack. “Our responsibility as designers, as communicators, as artists, as creators, is to inform people of the situation but then go further and give them the tools they need to take action.” This is what he believes Code of Conscience does: “It doesn’t just say there’s a problem, it says there’s a problem and here’s something we can do about it. In principle, anyone can pick up these tools and it’s empowering because it makes us feel like we all have a chance to make change. The biggest danger is the sense of paralysis when we learn about this issue, because it’s another form of denial so it’s important to have a balance of optimism and honesty.”

We often think activism means getting in the streets and risking arrest but it doesn’t, it can be writing a song, making a film or going into your community and making a communal garden, or it can be creating a piece of technology like Code of Conscience.

Change is on the horizon

Today, Hugo and Tim are excited that the Code of Conscience is now on the ground in the Amazon. “We’ve started the first trial with a government in South America,” says Tim. “It’s a process and we are moving towards our goal with positive intentions. This is activism.”

With strides forward being made, Deborah says they are using the positive momentum around the project to try to convince the fabricators of heavy machinery to adopt the technology. “I believe there are two ways in which this can happen: if one or two companies adopt the technology, we will have a signalling from the sector that this is important. But the dream would be for them all to adopt it and there’s no reason for them not to because it comes at zero cost,” she says. Were the latter to happen, a new level playing field would be created whereby Deborah adds, “all the companies producing these machines will continue to operate in the same competitive environment knowing that none of them are running the risk of seeing their machinery being destroyed or seized in situations that are contributing to deforestation and climate change.”